The Peremptory Challenge

As stated, the exclusion of persons from the jury based on essentially no reason at all is known as a peremptory exclusion or strike. The essential nature of the peremptory challenge is that it is one exercised without a reason stated, without inquiry, and without being subject to the court’s control.”[12] Generally, prosecutors are entitled to exercise these challenges “for any reason at all, as long as that reason is related to his view concerning the outcome” of the case to be tried.[13] However, the law forbids the prosecutor to excuse jurors solely on account of their race or on the assumption that Black jurors as a group will be unable to impartially consider the Government or State’s case against a Black defendant.[14] Likewise, the law forbids prosecutors to excuse jurors solely on account of one’s gender, for gender, like race, is an unconstitutional proxy for juror competence and impartiality.[15]

It is believed that prosecutors often try to exclude Blacks from juries, especially when the accused is Black because they are trained and admonished that no Black citizen could be a satisfactory juror or fairly try a Black defendant, and this phenomenon is unfortunately true whether the prosecutor is white or Black. This belief is based in part on an instruction book as used by the prosecutor’s office in Dallas County, Texas, that explicitly advised prosecutors that they are to conduct jury selection so as to eliminate “ ‘any member of a minority group.’, and an earlier treatise on jury selection circulated also in Dallas County, Texas, wherein the instruction was to not take Jews, Negroes, Dagos, Mexicans or a member of any minority race on a jury, no matter how rich or how well educated.”[16] An earlier jury-selection treatise circulated in the same county similarly instructed prosecutors thusly: “Do not take Jews, Negroes, Dagos, Mexicans or a member of any minority race on a jury, no matter how rich or how well educated.”[17] Although these writings surfaced in Dallas, Texas, it is opined that this was the training in most, if not all, of the courts in this country, and is still the prevailing thought today because, as Justice Marshall aptly stated, “a prosecutor’s own conscious or unconscious racism may still lead him easily to the conclusion that a prospective Black juror is “sullen,” or “distant,” a characterization that would not have come to his mind if a white juror had acted identically, and a judge’s own conscious or unconscious racism may lead him to accept such an explanation to justify exclusion as well supported.[18] This prejudicial exercise of peremptory challenges is not limited to prosecuting attorneys, however, as defense counsel can often employ this exercise when circumstances so allow.

If so inclined, prosecutors may challenge a defense counsel’s use of peremptory excuses of jurors because they have standing, and indeed an obligation, to assert the rights of the jurors sought to be excluded,[19]for the potential for racial prejudice inheres in the defendant’s challenges as well. However, if a prosecutor fails to challenge the defense counsel’s juror exclusions, this prejudicial exclusion goes unchecked. Thus, take for example a situation where there is a white defendant on trial for committing a crime against a Black person. The white defendant’s counsel may not want Black jurors from deciding his client’s fate, so he purposefully excludes Black jurors from sitting on the jury. Now, if the prosecutor fails to challenge these exclusions, the white defendant could potentially be judged by an all white jury, and the jurors could, no doubt, use their life experiences and beliefs during deliberations. These jurors could then decide not to convict based on an inherent belief and inclined view, as once held in this country by the Highest Court, that, “Blacks are regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior they have no rights which the white man is bound to respect.[20] Thus, I am resolute in the statement that, “peremptory challenges constitute a jury selection practice that permits “those to discriminate who are of a mind to discriminate,”[21] whether prosecutor or defense counsel – Black or white.

The Challenge For Cause

A challenge for “cause” is a challenge to the prospective juror’s qualification to sit on the jury either because s/he does not meet certain statutory requirements, or s/her has revealed a certain significant bias during questioning.

The excusal from service for “cause” can be based on a number of reasons including: the inability to read and write the English language; inability, by reason of mental or physical infirmity, of rendering satisfactory jury service;[22] having a charge for, or a conviction in a State or Federal court of record of a crime punishable by imprisonment of more than one year, and the person’s civil rights have not been restored;[23] being under indictment for a felony or misdemeanor, i.e., currently charged with a crime; insanity; a bias or prejudice in favor of or against the person accused; has made up his mind as to the innocence or guilt of the accused before trial commences; has a bias or prejudice on any phase of the law that either the prosecution or the accused may rely on; or has scruples against the imposition of any penalty, especially death, or may refuse to consider any area of punishment that the accused may be entitled to under the law. This is where the problem most often lies with minorities and people of color.

Far too often, we have an opinion that only God sits in judgment of people, and to this there is no argument. However, the system of jurisprudence we live under states that we are the ones who sit in judgment of the accused. Thus, when we give answers to questions about feelings toward various subjects as inquired of by counsel, such as, “I could not look past the fact that he had his pants hanging down”, or, “I could not get past the fact that he wore a hooded sweatshirt or played music too loud”, examples indicating a potential bias against the accused, or neglect the call to jury service altogether, we undoubtedly disqualify ourselves without even the slightest threat of further inquiry. When this is done, we cannot complain that justice was not served when a verdict of guilt comes down against a person of color because justice in this system is most often decided by juries.

The Jurors’ Bill of Rights

Perhaps the most important aspect of jury service is for jurors to be empowered with what is called the Jurors’ Bill of Rights. The Jurors’ Bill of Rights is an admonishment that a juror has the right to her own opinion, to inform the judge that she is being pressured to vote one way or another, and the right to think for oneself. The understanding of the Jurors’ Bill of Rights is of critical importance because a juror should not abandon views and life’s experiences when evaluating evidence simply because fellow jurors apply a different life experience to the facts. In other words, a juror should never go along just to get along, for to do so undermines the entire process and acts to invade the province of the individual juror.

At the conclusion of a jury trial, the judge gives an instruction to the jurors before they retire to deliberate. The most common initial instruction typically goes like this: “Your job is to decide the facts based on the evidence that you have heard and saw during the trial. The evidence includes the testimony of the witnesses and exhibits. You must consider all of the evidence. This does not mean that you must believe all of the evidence. It is up to you, and only you, to decide whether the testimony of a witness was reliable, as well as how much weight to give to the testimony. In deciding the facts of this case, you are the sole judges of the credibility of the witnesses. You will have to decide which witnesses to believe and which witnesses not to believe. In determining whether to believe any witness and evidence, you should apply the same tests of accuracy and truthfulness which you apply in your everyday lives.” Naturally, although not so stated, this typically means that a juror will commonly apply her/his own views and life experiences when evaluating evidence.

The judge will then instruct the jury on the law pertaining to the particular case, and instruct the jury to choose a foreperson. The jury is then dismissed and retires to decide the case. In all of the instructions given, however, often judges do not empower the jury of its Bill of Rights which is something that each juror should be acutely aware of during deliberations.

In instructing the jury, judges should further admonish the jury that, “jurors should consider the views of others with the objective of reaching a verdict, but should not surrender their own honest beliefs in doing so. Each juror must decide the case for her/himself, but only after discussion and impartial consideration of the case with fellow jurors. Jurors are not advocates for one side or the other. A Juror should not hesitate to re-examine her/his own views and to change her/his opinion if convinced s/he is wrong, but should not surrender an honest belief as to the weight and effect of evidence solely because of the opinion of fellow jurors or for the mere purpose of returning a verdict.”[24] This jury admonishment dates back to the 1800s when a judge instructed a jury that, “while, undoubtedly, the verdict of the jury should represent the opinion of each individual juror, it by no means follows that opinions may not be changed by conference in the jury room. The very object of the jury system is to secure unanimity by a comparison of views, and by arguments among the jurors themselves. It certainly cannot be the law that each juror should not listen with deference to the arguments, and with a distrust of his own judgment, if he finds a large majority of the jury taking a different view of the case from what he does himself. It cannot be that each juror should go to the jury room with a blind determination that the verdict shall represent his opinion of the case at that moment, or that he should close his ears to the arguments of men who are equally honest and intelligent as himself.”[25] Although aptly stated, it is opined that each juror must still stand on firm ground when convinced of her/his opinion of the facts and not abandon that ground simply to reach a verdict.

Juries must understand that they are a collective body, but a juror is an individual person. In this regard, a juror must not abandon her own beliefs if she is convinced of these beliefs regardless if her beliefs are contrary to the majority. Thus, when presented with evaluating evidence and applying one’s own common sense and experience to a situation, one should be mindful and careful to not abandon those beliefs because the deliberative process, while comprising of discussions of others, is still based on an individual’s own experiences. In other words, a juror should never subordinate her/his views to another especially if she/he is convinced of these views, as this is where jurors are to use their own common sense and apply life’s experiences when evaluating the facts presented.

As stated, judges should admonish the jury of the Bill of Rights prior to its deliberations. However, if a judge fails to so admonish the jury, it is counsel’s ultimate responsibility to empower them with these rights and to ensure that each have a clear understanding because the responsibility jurors undertake at this stage is critical. Thus, if a judge remains silent on this point, counsel’s voice should sound loud and clear.

Close

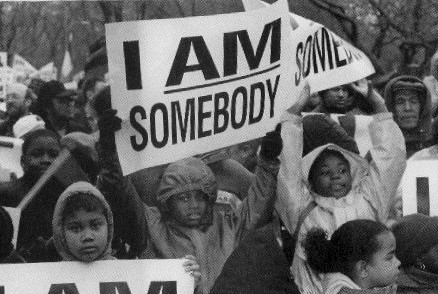

In 1880, the United States Supreme Court invalidated a state statute providing that Black citizens could not serve as jurors.[26] Thus, since that time, Blacks have been able to serve as jurors. However, all too often we want to get out of jury duty by rationalizing that we are too busy, we do not have time, we will lose our job, or any other reason that we can conjure up to get out of jury duty. When this is done, the fate of loved ones, friends, and persons whom we have grown an affection and appreciation for is more often left up to people who do not have our best interests at heart. This fate is left up to persons who are not our peers – persons who do not look like us, are not from the same neighborhood, do not live next door to us, and who do not share our life’s experiences. These people typically have their own agenda, and do not have an ear bent toward justice or mercy by our way. We seem to rationalize reasons for not wanting to serve on juries up until the point when it is a loved one of ours who is accused and stands in need of this “jury of peers”. Additionally, if we are not successful in dodging the jury summons and get to the courthouse, we talk our way off the jury and then complain of an unjust verdict. We sometimes make voluntary statements that disqualify us for cause. Thus, as a friend once told me about our people and jury service, if we are indeed desirous of sitting on a jury to attempt to exact justice or mercy, sometimes silence is best! This is not to say that simply showing up for jury service will guarantee our presence on the jury. Rather, as has been shown, there are a sundry of reasons why we may be excluded from service. However, if we ignore the summons altogether, we then strain to complain when a verdict is rendered that we find to be unjust or not in agreement with.

The Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad wrote in point number 2, under What the Muslims Want of the Muslim Program that, “We want justice. Equal justice under the law. We want justice applied equally to all, regardless of creed or class or color.”[27] Thus, in the context of jury service, it is opined that justice can only truly be served if we as a collective body decide that such service is not only a civic duty, but indeed a necessary obligation to our people. Only we can truly dictate whether an accused will be tried by a jury of his peers if we as a collective body decide that jury service is worth our time. As stated, there are a variety of mechanisms and tools used to keep Blacks and minorities off a jury, let us not give another reason for exclusion that remains unchallenged.

[1]U.S. Const. Amend VI.

[2] Holland v. Illinois, 493 U.S. 474 (1990).

[3] Black’s Law Dictionary, 6th Ed. (1990).

[4] Carter v. Jury Comm’n of Greene County, 396 U.S. 320, 330 (1970).

[5] Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400 (1991); Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 500 U.S. 614 (1991); and Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. 42 (1992).

[6] Strauder v. West Virginia, 10 Otto 303, 100 U.S. 303 (1880).

[7] Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 85 (1986), quoting Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 305 (1880).

[8] Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 155, 156 – 157 (1968).

[9] Black’s Law Dictionary, 6th Ed. (1990).

[10] Nebraska Press Assn. v. Stuart, 427 U.S. 539, 602 (1976) (Brennan, J., concurring in judgment).

[11] Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986).

[12] Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 220 (1965).

[13] Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 89 (1986).

[14] Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 89 (1986).

[15] J.E.B. v. Alabama, 511 U.S. 127, 129 (1994).

[16] Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 104 (1986) (Marshall, J., concurring in judgment), wherein Justice Marshall noted in note 3, that an instruction book used by the prosecutor’s office in Dallas County, Texas, explicitly advised prosecutors that they conduct jury selection so as to eliminate “ ‘any member of a minority group.’ ” Van Dyke, at 152, quoting the Texas Observer, May 11, 1973, p. 9, col. 2.

[17] Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 104 (1986), quoting the Dallas Morning News, Mar. 9, 1986, p. 29, col. 1.

[18] Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 106 (1986) (Marshall, J., concurring in judgment).

[19] United States v. DeGross, 913 F.2d 1417 (9th Cir. 1990).

[20] Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. 393, 406 (1856).

[21] Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559, 562 (1953).

[22] 28 U.S.C. § 1865(b)(4).

[23] 28 U.S.C. § 1865(b)(5); and United States v. Greene, 995 F.2d 793, 795 – 796 (8th Cir. 1993).

[24] Lowenfield v. Phelps, 484 U.S. 231, 234 – 235 (1988).

[25] Allen v. U.S. 164 U.S. 492, 501, 502 (1896).

[26] Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880).

[27] Elijah Muhammad, Message to the Blackman (1965).