Why Blacks Should Serve On Juries

“We the jury find the defendant, GUILTY!!!”

This is commonly known as the single word verdict. Many an accused fears hearing this word because it carries consequences that are often life altering. In some cases, the penalty can be as small as a fine, in instances such as a traffic violation, while in others, the penalty can be as severe as life imprisonment or worse – death. Nonetheless, despite the penalty to follow, this single word changes lives.

Often we wonder how a jury makes its decisions. Juries are often instructed to base decisions on facts, the law, and/or a combination of the two. However, juries often base decisions on their own life experiences, and they use this resource when evaluating the facts and law that they have been presented with during a trial.

But who is this jury? Are they peers? Where do they come from?

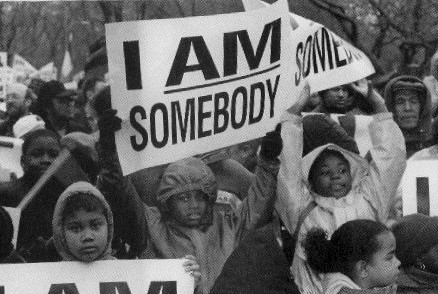

The purpose of this article is to attempt to explain rather simply the jury selection process, and how it supposedly works toward justice for the accused. It is hoped that after reading this article, the audience will be more informed of the process and inclined not to ignore that jury summons and be part of carving out justice and mercy where such is demanded in our community.

A Jury of One’s Peers

In a criminal setting, the 6th Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees the accused the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury of the State and District wherein the crime shall have been committed.[1] The Constitution, however, guarantees a right only to an impartial jury, not to a jury composed of members of a particular race or gender.[2]

A jury is defined as, “a certain number of men and women selected and sworn to inquire of certain matters of fact and declare the truth upon evidence to be laid before them. It is a body of persons temporarily selected from the citizens of the particular District, County, Parrish, Township, etc., and invested with power to present or indict a person for a public offense or to try a question of fact.”[3]

The very idea of a jury is a body … composed of the peers or equals of the person whose rights it is selected or summoned to determine; that is, of his neighbors, fellows, associates, persons having the same legal status in society as that which he holds.”[4] Although not included in the 6th Amendment, the phrase “jury of one’s peers” has been interpreted by courts to mean equal, i.e., the jury pool must include a cross section of the population of the community in terms of gender, race, and national origin. However, the jury selection process must not exclude or intentionally narrow any particular group of people. Although not the primary focus of this article, this jury concept also applies to civil trials, in that all litigants have a right to jury selection procedures that is free from state-sponsored group stereotypes rooted in, and reflective of, historical prejudice.[5]

More than a century ago, the United States Supreme Court decided that a State denies a Black defendant equal protection of the laws when it puts him on trial before a jury from which members of his race have been purposefully excluded.[6] However, this does not mean that a Black defendant has a right to a Black jury, as the High Court has held, a defendant has “no right to a ‘petit jury composed in whole or in part of persons of his own race,”[7] Rather, the supposed objective of the jury selection process is to select an impartial jury who will be fair, listen to the facts of the case, and render a verdict based on the evidence presented. And, although the Supreme Court emphasized that a defendant’s right to be tried by a jury of his peers is designed “to prevent oppression by the Government’s arbitrary exercise of power by prosecutor or judge”,[8] peer or equal does not mean equal in social, economic, class, race, or the ethnicity of the accused. Rather, the jury selection process contemplates only that random persons from the community or city, such as Houston, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York, etc., or surrounding counties where the crime was alleged to have been committed will be considered peers and they will sit in judgment of the accused. Simply put, it does not mean that if a Black man stands accused of a crime, other Black men from his socio-economic background with like experiences will sit in judgment of him.

Truly A Numbers Game

We have heard the term jury selection. However, this is a misnomer – jurors are not selected, they are excluded! The process varies depending on what State the case is tried in and if the case is a Federal or State matter. However, this article will focus on matters, either State or Federal, where the attorneys question prospective jurors. In these situations it generally works like this:

In any particular matter that is being tried to a jury, the clerk of the court assembles a list of potential jurors from voter registration cards, licensed drivers, etc. The clerk then mails a jury summons informing the recipient that h/she has been called for jury duty and to appear in court on a particular day and time. The potential jurors then sit in the jury assembly room for hours in some cases waiting to be called to a particular courtroom. The jurors chosen for a particular court are often chosen at random and given a number from 1 to as many as 60 depending on what the judge of the particular court has requested.

During the jury exclusion process, the attorney representing the accused and the prosecuting attorney have the opportunity to question the jury panel on a wide variety of topics designed to ascertain the juror’s individual views and opinions on matters that may come up during trial to determine if a person is fit to be a juror for that particular case. This is typically known as voir dire, which is a French term that means, “to speak the truth”,[9] and is said to, “provide a means of discovering actual or implied bias and a firmer basis upon which theparties may exercise peremptory challenges intelligently…and helps uncover factors that would dictate disqualification for cause.”[10]

Depending on responses to questions, jurors can be excused for “cause”, or they can be excused by either the defense counsel or prosecuting counsel for essentially no reason at all. This is known as a peremptory excuse. However, this reason for exclusion cannot be based on the juror’s race, ethnicity, national origin, or gender,[11] for jury selection may include no process which excludes those of a particular race or intentionally narrows the spectrum of possible jurors.

At the close of the questioning process, depending on whether the charge is a misdemeanor, in which case six jurors are seated, or a felony, in which twelve jurors are typically seated, both sides get the opportunity to excuse three or ten jurors from sitting on the jury. Then, the next unchallenged jurors, ones seated in numerical order, are the ones that will comprise the jury. Thus, if the first three jurors are excused by the defense counsel, and the next three are excused by the prosecuting attorney, the next persons as seated in numerical order are the persons who will be on the jury. Thus, in felony matters, the attorneys will often focus attention and question the first 35 seated persons, and in misdemeanor matters, the attorneys will generally focus attention on the first 15 seated persons.

This is a very informative piece. Thank you my Brother

Very informative article. It provides a different way of looking at jury service. Thank you